This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Ajay Mathur.

When you hear about polio, you may think of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose bout with the highly infectious disease left him paralyzed from the waist down, or the surge of polio in the early 1950s that stoked fear of the incurable and potentially paralysis inducing illness.

Today, polio is more than a part of our history – it’s a part of our today. The disease is making a comeback globally, with a case confirmed recently in the United States in Rockland County, NY.

In this blog, Dr. Ajay Mathur of ID Care gives an overview of what you should know about the polio resurgence.

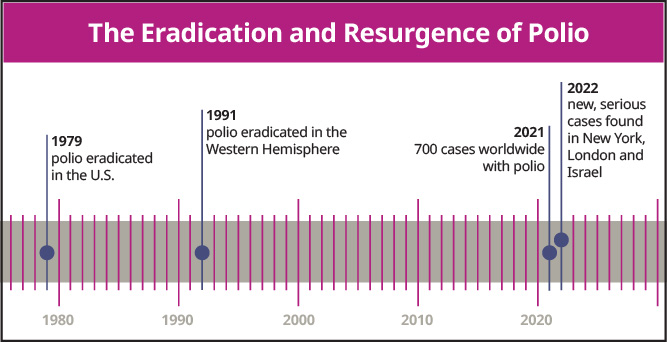

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is a syndrome that arises from the poliovirus and can have dreaded complications, most often in children under age 5. A worldwide problem for centuries, polio was eradicated in the U.S. in 1979 and in the Western Hemisphere in 1991 through an aggressive vaccination program. But in July 2022, a case of polio that caused irreversible paralysis was documented in Rockland County, New York, and hundreds of other people could be infected there. Additionally, a case was diagnosed in Israel this year and evidence that the virus is circulating in London was found in its sewers. In 2021, close to 700 cases of polio were recorded worldwide.

Polio is rebounding where populations have not been sufficiently vaccinated against the virus. Reasons include a poor health infrastructure and political unrest in some places, especially Afghanistan and Pakistan; worldwide COVID-19-related interruptions in polio inoculation that may take years to rectify; and vaccine hesitancy, which is a concern in the United States.

“Some people think that polio is not a U.S. illness, so they wonder why they need to get vaccinated against it,” Dr. Mathur said. “But the reason it’s not prevalent in the U.S. is that we have high vaccination rates. If we didn’t all vaccinate against polio, it would come back, just like it has in other parts of the world.”

What are the Symptoms of Polio?

About 70% of those who contract polio are asymptomatic. Another one-quarter of people with polio experience flu-like symptoms, which can include:

- Malaise

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Neck stiffness

- Muscle pain

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Low fever

- Sore throat

“Rarely, serious complications can arise from polio,” Dr. Mathur said. “One is aseptic meningitis, a viral inflammation of the brain and spinal cord that usually goes away in about a week. But the most dreaded complication is irreversible muscle paralysis that can range in severity, which happens in about 1 of every 200 cases. In addition to the legs, the paralysis can affect the muscles involved in breathing.” While cases with paralysis in breathing muscles can result in death, this is rare.

Understanding Post-Polio Syndrome

Unfortunately, those who have recovered from polio may develop symptoms again later. Post-polio syndrome can surface 15 to 40 years after the original illness, bringing:

- Joint pain

- Muscle weakness

- Fatigue

- Worsening of existing paralysis

- New paralysis, muscle weakness or muscle atrophy

- Difficulty breathing

“Symptoms of this non-contagious syndrome are often most severe in those who recovered well from serious initial polio complications,” Dr. Mathur said. “Although its cause isn’t fully understood, experts believe that post-polio syndrome arises due to deterioration of new connections between nerve cells and muscle fibers that were generated by the body during recovery.”

Who is at Risk for Polio?

Those at highest risk of contracting polio risk are people who are not vaccinated against the disease. Among the unvaccinated, people who have weakened immune systems face the highest risk of getting polio and its most severe complications. They include:

- Very young children

- Elderly people

- Pregnant women

- Those who have HIV or are taking steroids long-term

- Lab workers who handle throat and stool samples, underscoring their need for proper protection measures

How is Polio Spread?

People contract polio through the fecal-oral route, meaning that they come in contact with germs from the stool of someone who has the virus. This can happen when an infected person fails to engage in sufficient hand washing after using the bathroom and then touches or cooks food for someone else.

Once polio enters the body through the mouth, it travels through the esophagus and stomach, where it replicates within the GI tract. It can then make its way through the bloodstream into the central nervous system and spinal cord, where it can lead to paralysis.

“Once the virus finds its way into nerve cells and then the spinal cord, it’s nearly impossible for the body to eradicate it with an immune response,” Dr. Mathur said. “This affects the nerve cells emanating from the spinal cord in a process that does not stop, which is why we often don’t see a full resolution of symptoms.”

What Constitutes a Polio Epidemic?

In places where polio has been virtually eradicated, even a small number of cases can be considered an epidemic if they are associated with paralysis, Dr. Mathur said.

“If you see five or 10 acute cases in a community where you don’t often see polio, and they’re multiplying, that would suggest an epidemic,” he said. “Fortunately, we are not seeing a polio epidemic in the U.S.”

Vaccinating Against Polio

There are two types of polio vaccines, and they work differently in the body.

The only vaccine type given in the U.S. is made from an inactivated form of polio, and creates antibodies in the bloodstream that cause the immune system to attack if polio enters the body. This vaccine doesn’t stop people from getting polio, but confers lifelong immunity against the disease’s most severe complications.

An oral vaccine, given in most of the world, is made from a weakened but live version of the polio virus. That vaccine also works by generating antibodies, but within the GI tract rather than the bloodstream.

Fighting Two Kinds of Polio

Polio vaccines were developed to fight naturally occurring, or “wild-type,” polio, which has been present across the globe for centuries. But another type of polio has cropped up that is associated with the oral vaccine.

The live virus, used only in the oral vaccine, can mutate into “vaccine-derived polio” in the GI tracts of individuals who received this oral vaccine. While people who receive the live polio vaccine cannot get polio from the vaccine itself, they may end up shedding vaccine-derived polio in their stool, which could infect the unvaccinated people around them.

It’s important to know that this issue is never associated with the inactivated vaccine administered in the U.S., which has been used exclusively across America since 2000.

Establishing Herd Immunity

Nevertheless, vaccine-derived polio does occasionally emerge in unvaccinated people in the U.S., either because they’ve traveled to a country that uses the oral polio vaccine or because they’ve interacted with others who have traveled to those countries closer to home.

That’s a good reminder of why thorough vaccination across whole populations is so important.

People who are fully vaccinated against polio are nearly 99% protected from its most severe complications. And if an area’s vaccine rate is high, with at least 80% of the population inoculated, the whole population will likely remain free of the symptoms or complications of polio, even if a few individuals are shedding the virus.

“New cases of polio are only a concern if vaccine penetration isn’t high enough at the population level,” Dr. Mathur said. “That’s exactly what caused the vaccine-derived case in Rockland County, where rates of vaccination against polio are around 60%, and it’s an example of why establishing herd immunity is so crucial.”

When Should Polio Vaccines be Given?

In the U.S., pediatricians give the inactivated polio vaccine as a series of four. After the third shot, the immune system is prepared to attack if polio enters the body, and after the fourth shot, individuals gain lifelong immunity against severe complications of polio.

“The vaccines are safe for children,” Dr. Mathur said. “The worst side effect someone might get from a polio vaccine is a sore arm. There are no long-term ramifications or downside if we all get vaccinated, especially because the shots we use in the U.S. can never cause vaccine-derived polio.”

But when is the polio vaccine given? In the U.S., children start the series at around 2 months of age and conclude it before they are 6 years old.

“If people get the series later, it’s still effective,” Dr. Mathur said, “but we do it when children are younger because they are the most vulnerable to complications.”

Although vaccine formulations and schedules may have been different decades ago, anyone raised in the U.S. who was inoculated against polio likely has lifelong protection against major complications. Exceptions are healthcare workers and people traveling to countries with higher rates of polio. For those individuals and people in close contact with them, an adult booster of the inactivated polio vaccine may be necessary.

“Who should get boosted is a work in progress,” Dr. Mathur said. “We will know more as epidemiologists figure out how widespread polio is and who is most at risk of complications as they age.”

Diagnosing Polio and Tracking its Spread

Polio isn’t easily found in the blood, raising the question: Is there a test to diagnose polio? To diagnose the virus, infectious disease doctors like those at ID Care take throat or stool cultures from patients.

“The doctor needs to alert someone at the lab level so that specialized testing of the samples can be conducted,” Dr. Mathur said. “In addition, the state has to be involved so there’s a record of any polio cases diagnosed, enabling efforts to prevent and track spread.”

Because the infection is transmitted through stool, a key way to track polio’s spread through a community or region is by testing wastewater for evidence of the poliovirus. Officials have been evaluating polio levels in Rockland County and surrounding areas since the recent case there, and experts have been conducting similar testing in the sewers of London.

Treating Polio

There is no cure for polio and no treatments have been developed, so the illness is treated supportively. Physical or occupational therapy can help patients regain function after paralysis by training unaffected muscles to compensate for those that have been paralyzed. Medical management by infectious disease doctors like those at ID Care, sometimes in collaboration with neurologists, may help ease other symptoms.

ID Care: Experts in Polio Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment

So far, ID Care has not seen any cases of polio, and the practice hopes that will continue.

However, because ID Care’s New Jersey offices aren’t far from New York, the more than 50 infectious disease doctors within the practice have supplemented their knowledge about polio by studying the Rockland County case. They know what to look for in patients suspected to have the illness, as well as how to approach diagnosis and treatment.

ID Care doctors can see patients with potential polio symptoms in any of their 10 offices. In other cases, the doctors might consult with hospital medical teams to help diagnose patients admitted with muscle weakness. “We would be involved in ordering tests and telling the lab that the case could be polio,” Dr. Mathur said.

Anyone concerned about a potential case of polio should see a doctor as soon as possible. In addition, anyone planning a trip to a country where polio is prevalent can visit doctors at ID Care for a pre-travel appointment to determine if they need a polio booster vaccine.

To schedule an appointment with an ID Care infectious disease doctor today, call 908-281-0610 or visit idcare.com.