This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Richard Krieger.

While most people have heard of rabies infections among animals such as raccoons or dogs, rabies in humans is fortunately rare. Only about three people per year are infected in the U.S. Nevertheless, because the symptoms of untreated rabies are universally fatal, many people are unusually afraid of the disease. Some fact-based understanding, however, can put these fears into proper perspective and give you the best chance of staying rabies-free.

In this blog, ID Care infectious disease specialist Dr. Richard Krieger shares his expertise about this unusual disease that is spread by the bite of an infected animal, providing what you need to know to deal with rabies in the U.S., as well as in developing countries where it is more prevalent. You’ll learn about important aspects of rabies, including:

- What is it?

- Which animals carry it?

- How is it transmitted?

- What are the signs and symptoms?

- What should you do if bitten or scratched by an animal that might have rabies?

Worldwide, about 59,000 people die from rabies each year. While that’s a big number, in a world of nearly 8 billion people, such a relatively low mortality rate for a completely fatal disease (if untreated) makes rabies a rare infectious disease globally.

According to Dr. Krieger, “rabies is talked about more than seen, and the incidence in the U.S. can be counted on one hand, but it is higher in less-developed areas around the world. As a result, we do see patients who acquired rabies while traveling or who’ve immigrated to this country with the disease.”

Protecting yourself from rabies starts with vaccinating pets, avoiding contact with wildlife and unknown domestic animals, and getting prompt medical care after any suspected exposure — before the onset of symptoms when treatment becomes ineffective. What you need to know about rabies can make all the difference in preventing this deadly infectious disease.

What Is Rabies and How is it Transmitted?

The Rhabdoviridae family of viruses includes the genus Lyssavirus, in which the rabies virus is classified. It is carried in nervous system tissue and saliva, which is why a bite is usually needed for the virus to transmit from one animal to another. Rabies then travels through nerve tissue until it reaches the brain, where it causes tremendous central nervous system disruption and eventual death.

According to Dr. Krieger, “it’s almost impossible to get rabies from an animal without contact between infected saliva and broken skin. In a few rare instances, organ recipients have gotten it from organs transplanted from people who unknowingly died of rabies, but nearly all cases of animal-acquired human rabies stem from animal bites.”

Why Rabies is a Zoonotic Disease

Zoonotic means a disease that spreads predominantly from animals to humans, and less so from humans to humans. While rabies is a classic example, anthrax, plague, and many other diseases transmit zoonotically. In the same way influenza and now COVID-19 are endemic to the human population, rabies is floating around the animal world and could be present anywhere.

Which Animals Carry Rabies?

“In the Northeast and along most of the East Coast,” Dr. Krieger warns, “the biggest rabies reservoir is the raccoon population. When they come in close contact with other animals, usually foxes, skunks, groundhogs, or other raccoons, they can transmit rabies. But they can give it to any mammal.”

Most animals will die of a rabies infection within a few weeks or months. Raccoons, however, can carry the virus for a year or more before exhibiting symptoms. They are contagious that whole time, and females can even pass the virus to their young.

The other big North American rabies reservoir is bats. According to the CDC, bats are the leading cause of rabies transmission to humans in the U.S. Outside this country, bites from rabid, stray dogs account for the vast majority of rabies infections in humans.

Where is Rabies Most Common?

With wild animals like bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes the most likely carriers in the U.S., wherever these animals are present, so is rabies. In most of the rest of the world, however, rabies is still carried predominantly by dogs, and most global rabies deaths are caused by dog bites. Of all human deaths due to rabies, 95% occur in Asia and Africa.

Rabies flourishes especially well in developing countries with limited healthcare access, and where effective animal vaccination is just not possible due to logistics or cost. In the U.S., human rabies cases have dropped from about a hundred per year before 1990 to fewer than five now.

“In this country,” said Dr. Krieger, “we get rabies mostly from wild animals and much less so from dogs, because our dogs are required to be vaccinated. In places with a lot of unvaccinated stray dogs, canine rabies is the most common vector by which the disease passes to humans.”

If you plan to travel through such areas, check first with the Centers for Disease Control for current rabies warnings, and take extra precautions to avoid exposure.

Who is at Greatest Risk for Contracting Rabies?

Anybody who comes in direct contact with mammalian animals faces some risk of rabies, and it rises as animal interactions increase. This includes hunters, hikers, landscape workers, farmers, ranchers, and zoo and veterinary workers, among many others.

The other category of concern is people traveling internationally where stray dogs and canine rabies are rampant. This includes large swaths of the developing world, but also certain areas in industrialized countries. Check the online CDC’s Travelers’ Health page for the latest rabies and other health alerts for your destination(s), but no matter where you travel, do not approach, pet, or feed unknown animals.

Those at the highest risk for rabies are encouraged to get a prophylactic (preventative) rabies vaccine, though it is not recommended for the general population or for people at low to moderate risk.

What Are the Symptoms of Rabies?

Typically after a bite from a rabid animal, rabies can take weeks or months to move through nerve tissue to reach the brain, where it will begin to produce symptoms. If not stopped with post-exposure prophylaxis in that treatment window, a flu-like illness will ensue with fever, headache, weakness, and nausea. This progresses to cause increasingly worse neurologic symptoms, including hallucinations, delirium, and insomnia. Patients may also notice numbness, discomfort, or itching in the bite area. Eventually, the milder symptoms lead to seizures and coma.

“In a full-blown case,” said Dr. Krieger, “patients experience hydrophobia, where drinking water or even the thought of drinking liquids causes spasms in the throat, so they stop drinking and eating, which leads to further deterioration. Eventually, inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) will cause death. It’s not a very nice disease, but it can usually be avoided with common sense and stopped with quick medical care.”

Rabies Diagnosis

Rabies testing is done through a tissue sample or biopsy, usually of the neck, to see if traces of the virus are present. There is no reliable blood test.

A diagnosis is usually made through a patient history and clinical examination, though some cases of rabies have gone undetected until a post-mortem exam. This is usually because the patient had no known animal contact and rabies was not suspected until after an unexplained death.

Often in such cases, there actually was animal contact with a bat. Their bites are usually painless, so the patient is unaware of a rabies exposure while sleeping. Nowadays, if you wake up with a bat in your bedroom, the recommendation is to catch the bat and have it tested for rabies. If this is not possible, you may be prescribed rabies prophylaxis treatment just in case.

How Do You Prevent Getting Rabies?

Vaccination can protect pets and high-risk humans from rabies, and prompt and thorough bite-wound cleaning and prophylactic antibody and vaccine treatment can prevent the virus from causing disease in previously unvaccinated humans. But nothing works better than avoiding the bite in the first place. This is especially true when traveling outside the U.S., where stray dogs are the primary rabies vector.

Dr. Krieger warns that “if you travel outside of this country, particularly to a developing country, stay away from dogs, especially stray dogs, because you just don’t know which are rabid. Consider them like you would lions or grizzly bears and keep your distance.”

What Should You Do If Bitten by a Rabid Animal?

Not every rabid animal bite is capable of causing infection. Dr. Krieger advises that “even if you are bitten by a rabid animal, often there may be not enough virus in the saliva, not enough saliva in the bite (a dry bite), or too much gets absorbed by clothing to transmit the virus.”

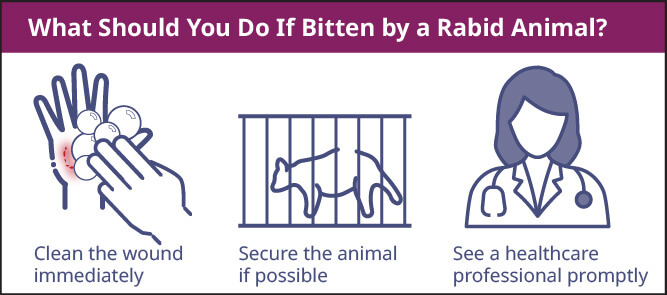

However, if there’s a chance the animal that bit you is carrying rabies, Dr. Krieger advises the following steps to prevent developing the disease:

- Clean the wound immediately and well with lots of soap and water. Washing out the infected saliva will significantly reduce your chances of getting the disease.

- Secure the animal if possible, and if the animal that bit you is recoverable, place it in a cage or pen and watch to see if rabies symptoms appear.

- See a healthcare professional promptly, such as the infectious disease doctors at ID Care. You may need prophylactic rabies vaccination and treatment.

Rabies Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: Vaccine and Immunoglobulin

After cleaning the wound, the second method of post-exposure rabies prophylaxis involves a two-medicine, multi-shot inoculation. The first injection is rabies immunoglobulin, the antibody given when somebody arrives at the emergency room after a bite from an animal that could have rabies. The injection will help contain and defeat the virus inside the body. The second drug is the rabies vaccine, which will spur the body to produce its own antibodies to protect against future infections. The vaccine is delivered in four or five shots within a month.

Ideally, post-exposure prophylaxis should begin on the day of the exposure, that is, the day the patient is bitten. However, the incubation period for rabies is an average 20 to 90 days, and the treatment can be effective as long as symptoms have not yet begun.

“The big advantage we have in fighting rabies,” said Dr. Krieger, “is that it’s a slowly developing infection, so there’s a fairly wide timeframe in which to administer the prophylaxis and it will still be effective — obviously the sooner the better, but if somebody is bitten and asymptomatic and they find out later that the animal was rabid, it’s not too late to take the vaccine.”

Is the Rabies Shot Painful?

According to Dr. Krieger, “we get shots for lots of things and nobody likes them, but rabies shots are not any worse than the other inoculations we give. Sensitive people may experience some typical short-term vaccine side-effects like arm soreness, fever, aches, and lethargy, but that’s about it.”

Older people may recall the outdated rabies prophylaxis known as the purified duck embryo vaccine (PDEV), made in duck eggs from killed rabies virus. It required more than 20 intraperitoneal injections to ensure proper absorption, and most people found it quite unpleasant. About 40 years ago, the duck embryo vaccine was replaced by modern rabies vaccines, which are a big improvement and about as distressing as a flu shot.

What is ID Care’s Role in Managing Rabies Risk?

Dr. Krieger recommends that, “if you expect a high risk of rabies exposure, regardless of where you’ll be, see us first for a protective rabies vaccine. If an unvaccinated person has an active case of symptomatic rabies, sadly, that’s a rare situation where there’s not much an infectious disease specialist can do. We can give palliative care to make them comfortable, but the prognosis is not good.”

However, if someone has suspected rabies but has not yet developed symptoms, ID Care doctors will advise and administer immediate treatment with the prophylactic vaccine and antibodies. These are nearly 100% effective if given properly and soon enough.”

Beyond that, ID Care’s role is largely in educating our communities about how to deal with a rabies infection and prevent transmission of the disease — if bitten, wash the wound and seek prompt medical care; if not bitten, avoid unknown domesticated animals and all wild ones. This is especially true of bats and racoons inside the U.S. and stray dogs in other countries. With effective prophylactic medicines, a bit of knowledge, and some common-sense precautions, you can help keep yourself safe and make rare cases of human rabies in the U.S. even rarer.

At ID Care, your health is our priority. If you have questions about rabies or any infectious disease, please call us at 908-281-0610 or visit idcare.com.